Broken truss-rod replacement

Truss-rods can fail. Sometimes because of over-tightening, sometimes when the hexagonal keyway has been rounded (with an undersized or worn allen key), sometimes when they rust and seize after being kept in damp conditions, and sometimes because they were under-engineered in the first place. And sometimes for no obvious reason.

I now grease all truss-rod threads, so that even should the guitar be kept in damp conditions (which of course it shouldn’t for several reasons), the threads should not rust. And should turn more easily in all conditions.

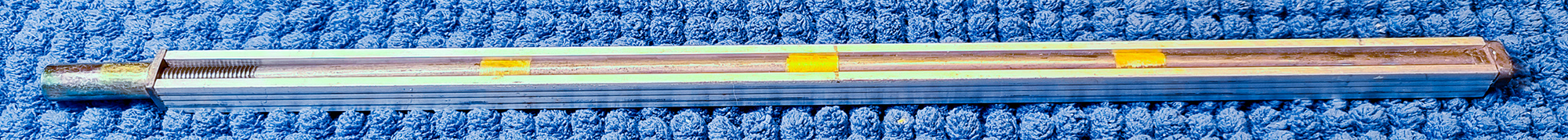

Daniel Clark recently sent me his 1989 Model 1 guitar with a non-functioning truss-rod. This truss-rod was made of a steel rod in an aluminium channel, as were most at the time of building. One end of the rod is fixed to the end of the channel, the other is threaded with a long Allen nut working against the other end of the channel.

Tightening the long nut against the threaded end of the rod shortens it, and as the channel is of fixed length, the channel has to curve. Because the truss-rod is tightly enclosed, it bends in its entirety with the longer channel back to the outside of the shorter rod, bending the neck with it.

Old type steel and aluminium truss-rod

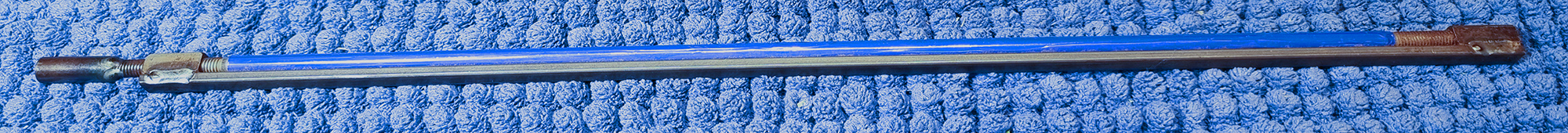

Modern truss-rods are simpler and more compact. The rod is threaded at both ends, one standard and one reverse thread, and runs through long nuts attached to each end of a narrow flat steel bar. So turning the rod (with an Allen key in the rounded end) one way shortens it (and the other way lengthens it) against the fixed length bar, thus bending it.

Not only does this have less work to do (not having to bend the sides of the channel), it also eliminates the problem caused by different expansion rates of steel and aluminium. It also permits pulling the neck forward if required.

Modern double action all steel truss-rod

Modern double action all steel truss-rod

When Daniel’s guitar arrived, turning the long Allen nut was effortless but had no effect. So the truss-rod had to come out.

The standard procedure is to remove the fingerboard (complete with frets), so the truss-rod can be changed, replacing the fingerboard afterwards. My problem with this method is that it damages the finish, not only between the fingerboard and the neck but also, more importantly, between the upper portion of the fingerboard and the soundboard. Touching up old finish on a soundboard is a problem, it will always show. So I decided on a different method.

Rather than remove the whole fingerboard, I take out the frets and cut a slot in the fingerboard above the truss-rod so I can remove and replace it. I do this with a router mounted on a simple plywood jig.

1. Here is the jig mounted over the fingerboard. I removed the frets and routed out the area above the broken truss rod, enabling me to lever it out. The mahogany neck is visible at the bottom of the slot. The old truss-rod is alongside.

2. The new truss-rod is in place. As it is narrower than the original, I set pieces of Blackwood on either side so the truss-rod is a snug fit. As the rod underneath now has to turn, it is lubricated with graphite powder to minimize resistance.

3. I cut a piece of ebony of the exact size to fit the slot and fitted and glued it in place, pressing it gently onto the truss-rod. I checked that the truss-rod can still turn freely.

4. I trimmed the ebony insert down to match the level of the existing fingerboard, cut the fret slots in it, and replaced the centre Mother of Pearl dots.

5. The old frets were worn, so after checking the fretboard is level, I replaced them with Evo Gold fretwire. This is much harder than the original nickel silver and will last much longer without pitting.

6. Now strung up, it needed just a tweak on the truss-rod, and it’s perfect. The only way the repair shows is that the new ebony is a little blacker than the original, but a quick oiling minimizes even this. With the 3rd and 4th strings over the joins, it is almost impossible to see. And no damage to the finish.

Click on the image to see a larger version.